This is the sixth in a series of excerpts from “A Journey of Faith for 150 years: A history of the Princeton United Methodist Church” by Ruth L. Woodward, Copyright 1997.

Thomas O’Hanlon’s preaching results in “the greatest outpouring of grace” but trustees can’t meet payroll

In November 1859 a committee was again appointed to investigate a course of Lectures for the benefit of the church. In February 1860 it was announced that $50 had been netted from the lecture series. In December an application was granted for a Singing School to hold sessions in the Lecture Room; however, permission was soon revoked as the school failed to comply with whatever conditions had been set.

In 1860 the Annual Conference appointed the Reverend John W. Kramer to the Princeton charge. However, he resigned after five weeks to take a position with the Seaman’s Friend Society and the Reverend Isaac Wiley was appointed in his place.

Wiley had spent three years as a medical missionary in China; at a time when few people travelled very far from home he must have had many interesting anecdotes. He spent the usual two year tenure in Princeton. In 1872 he was elected a Bishop of the Methodist Episcopal Church. A committee had been appointed to find housing for Kramer, but since Wiley was a widower the need for a parsonage could be postponed.

In December 1860, in anticipation of the spring meeting of the Annual Conference the Trustees “suggested” that they be provided with an unmarried man “as will suit our wants.” When notified that there was no unmarried man in the Conference who would be suitable for their needs, they requested, if possible, the appointment of Thomas O’Hanlon, then serving in New Brunswick. Since O’Hanlon received a bachelor’s degree from the College of New Jersey in 1863 he must have been attending classes during his ministry in Princeton.

Whether the special needs of the church were a revival of spiritual life, the raising of funds, or both, Thomas O’Hanlon seems to have been the right man. O’Hanlon was a warm and gifted speaker, and the Princeton church is said to have experienced the greatest outpouring of grace in its history during his pastorate. Hundreds of people are said to have responded to his call and “bowed the knee” at his meetings. Church records do not reflect that great an influx of new members; perhaps many united with other churches and for others it may have been only a temporary enthusiasm.

O’Hanlon apparently also had ideas about fund raising. In the spring of 1862, when funds were very low, he set forth a financial plan that listed amounts to assesseach member, presumably based on estimates of income. Assesments ranged from $1.00 to $50.00, with the average ranging between $5.00 and $8.00. If this method had worked it would have been possible to pay the pastor’s salary of $500 and parsonage rent of $135, as well as salaries for the sexton, presiding elder, and collectors. Class leaders were to inform members of their assessments and make collections. These monies were over and above pew rents, which members were urged to pay in advance, if possible. A list is available showing which pews rented for $5, $6, $8, $10, $15, and $20 respectively, but it is impossible to determine what factors determined desirability. Size may have been a factor, as well as closeness to the preacher, distance from a draft, etc. Besides the assessments and the pew rents, members were asked to contribute to a penny collection to help pay for light and fuel.

The trustees still had to grapple with other day-to-day problems. In July 1862 a committee was appointed to select the proper site for a privy in the rear of the church; the privy was completed by September. Later in the fall four tons of coal had to be purchased and a committee was appointed to solicit. subscriptions to pay for this necessity.

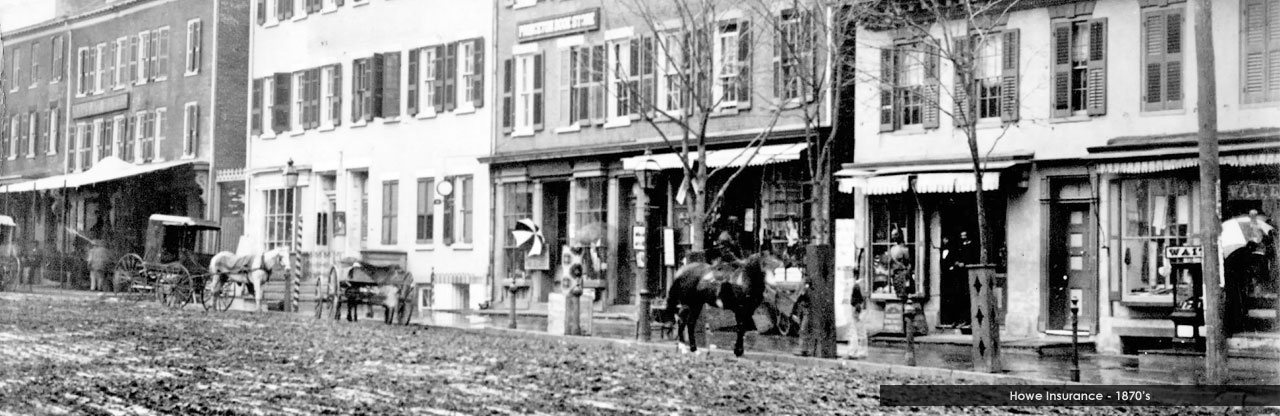

That year the church received some unwelcome notoriety when, on the evening of November 13, Charles Lewis, a drifter in town, temporarily left his horse and wagon in the church’s horse sheds. Lewis was later convicted of the murder and robbery of James Rowand, a jeweler and watchmaker. As Rowand walked from his shop on Nassau Street to his home, just beyond the cemetery on Witherspoon Street, he received a blow from a heavy club which fractured his skull.

On January 2, 1863 it was resolved to make Bro. O’Hanlon a “Donation visit.” It is not known whether this was to solicit a donation or to pay a portion of the’ pastor’s salary, but funds were very low. The following month the Treasurer, who showed a balance of $24.24, was ordered to pay the Sexton $25 on account of his salary. In March it was noted that insufficient money had been collected from pew rents to pay the minister’s salary, and in May, at a congregational meeting held after the Sabbath service, it was resolved, that in the future pew rents would be collected monthly in advance.